Interstellar comet 3I/ATLAS spews water like a cosmic fire hydrant

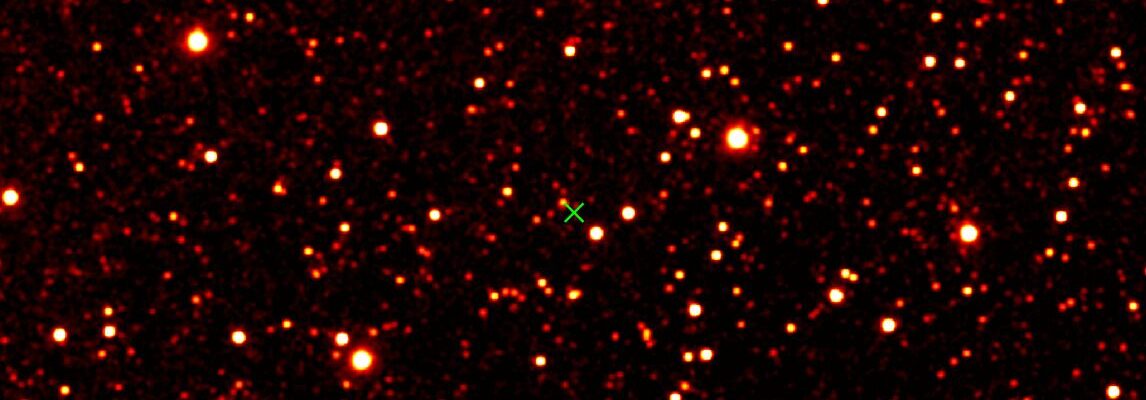

Comet 3I/Atlas continues Full of surprises In addition to being only the third interstellar object ever discovered, new analysis shows that it is producing the greenhouse gas hydroxyl (OH), compounds that indicate the presence of water on its surface. The discovery was made by a team of researchers at Auburn University in Alabama using NASA’s Neale Girls Swift Observatory and described in a study published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

Hydroxyl compounds can be identified by the ultraviolet signature they produce. But on Earth, many ultraviolet wavelengths are blocked by the atmosphere, which is why the researchers had to use the Neill Girls’ Swift Observatory — a space telescope free from the interference experienced by ground-based observatories.

Almost every comet seen in the solar system contains water, so the chemical and physical reactions of water are used to measure, catalog and track these celestial bodies and how they react to the sun’s heat. Finding it in 3I/ATLAS means that you can study its properties using the same scale used for ordinary comets, and this information could in the future be useful data for studying the processes of comets originating from other star systems.

“When we detect water—or even its weak ultraviolet echo, OH—from an interstellar comet, we’re reading a note from another planetary system,” Dennis Budowitz, a physicist at Auburn University who collaborated on the research, said in a press release. “This tells us that the chemical ingredients of life are not unique to us.”

Comets are icy masses of rock, gas, and dust that usually orbit stars (with the exception of the three interstellar objects found so far). When they are far from a star, they are completely frozen, but as they get closer, solar radiation heats and sublimates their frozen elements – turning them from solid to gas – and some of this material is emitted from the comet’s nucleus thanks to the star’s energy, forming a “tail”.

But with 3I/ATLAS, the data collected revealed an unexpected detail: OH production by the comet was already occurring farther from the Sun—when the comet was more than three times farther from Earth than the Sun—in a region of the Solar System where temperatures are not usually high enough to easily produce ice sublimation. However, already at that distance, the 3I/ATLAS was leaking water at a rate of about 40 kg/s, a flow comparable – the study’s authors explain – to that of a “hydrant at full capacity.”

These details appear to indicate a more complex structure than is typically seen in comets in the Solar System. It could be explained, for example, by small pieces of ice breaking off from the comet’s core, which are then vaporized by the heat of sunlight and feed the gas cloud that surrounds the celestial body. This is something that has so far only been observed in a small number of very distant comets and could provide valuable information about the processes that gave rise to 3I/ATLAS.

“Every interstellar comet so far has been amazing,” Auburn University researcher and co-author of the discovery Zexi Xing said in a press release. “Omoamoa was dry, Borisov was rich in carbon monoxide, and now ATLAS is releasing water at a distance we didn’t expect. Each is rewriting what we thought we knew about how planets and comets form around stars.”

This story appeared first wired Italy and translated from Italian.